What new aspects does the technical framework of machine learning bring to art-making? And conversely, what can artworks that use AI point to in AI research and development? These questions formed the basis for discussion during an online panel event, convened by the Creative AI Lab in collaboration with the NYU Digital Theory H-Lab for Frieze Week 2020, with Leif Weatherby, Nora Khan, Joanna Zylinska and Murad Khan. The full event can be viewed as a video here.

The Creative AI Lab is a collaboration between the R&D Platform at Serpentine Galleries and King’s College London’s Department of Digital Humanities. It follows the premise that collectively, we are at the early stages of understanding the aesthetics of ‘AI’: locating a new poetics, investigating what it means to work with systems that are able to calculate meaning, and practicing art-making in the so-called ‘black box’ of machine learning. This panel formed part of an ongoing and collaborative investigation into AI aesthetics, one of multiple lines of inquiry explored by the Lab. The event was hosted by the Lab’s principal investigators Dr Mercedes Bunz, Senior Lecturer in Digital Society, KCL, and Eva Jäger, Assistant Curator of Arts Technologies, Serpentine. A reader of the panellists’ work accompanied the event –– it can be downloaded from the Serpentine’s website. As Eva Jäger outlined, ‘the Lab holds space for this work, convening diverse conversations, like this one, and compiling a database of tools and resources. The lab also produces knowledge and approaches to digesting and communicating this media through experimental research projects’.

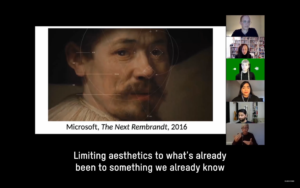

‘It’s not just a black box, It’s at least grey. When you open that up you start to see things that have either aesthetic value, critical value, or both’. This initial provocation from Leif Weatherby (NYU Digital Theory H-Lab) aligned with the impetus for such practices outlined by Mercedes Bunz: that ‘we need to reflect on the societal impact of this technology critically, but also on its creative capacity – art is offering a space for the creative and playful exploration of this technology’.

The panel responded to these considerations alongside a tele-present audience through presentation and discussion. A range of divergent approaches emerged for understanding the reciprocal relationship between AI and artistic research, encompassing philosophical, art historical and conceptual-technological approaches. In particular, two often overlapping modes of practice: working with machine learning to develop a distinctive machinic aesthetics through the generation and display of ‘front-end’ imagery, and works which foreground conceptual exploration, revealing ‘back-end’ processes and mechanisms.

Joanna Zylinska, Professor of New Media and Communications at Goldsmiths, University of London focused on the possibility that a shift in trajectory is required in AI art research, away from the binary view of humanity and technology. Critically questioning the motivations behind AI art production and its market, which in her view often reproduces persistent and ‘seductive’ human notions of creativity, she posited the possibility that contemporary machine learning practices should in fact tend towards a different “AI” – art for ‘another intelligence’, exemplified by Katja Novitskova’s work Pattern of Activation (2020).

Continue reading “Creative AI Lab – ‘Aesthetics of New AI’ panel discussion for Frieze Week 2020”

Like many parts of our lives, the cultural artifacts that shape our imaginations – films, books, and so on – are shaped by relationships of race. Join us for a free-wheeling conversation between Black speculative fiction authors, Hamza Mohamed and Ayize Jama-Everett, for an exploration of the role and importance of Black voices in shaping our collective imaginations of the present, and possible futures.

Like many parts of our lives, the cultural artifacts that shape our imaginations – films, books, and so on – are shaped by relationships of race. Join us for a free-wheeling conversation between Black speculative fiction authors, Hamza Mohamed and Ayize Jama-Everett, for an exploration of the role and importance of Black voices in shaping our collective imaginations of the present, and possible futures.