This is a collection of blog posts members of the department contributed to the annual Day of Digital Humanities, a global online event which was this year themed on ‘multilingual digital humanities’. These were originally published on the Language Acts & Worldmaking website at

https://languageacts.org/blog/day-of-digital-humanities-part-1/ and https://languageacts.org/blog/day-of-digital-humanities-part-2/

Introduction by Paul Spence

This year’s Day of Digital Humanities event Day of DH 2021 presents another opportunity to engage with the wider digital humanities community through a series of interactions channelled through Twitter and Instagram with the hashtag #dayofdh2021. The focus this year is on ‘multilingual DH’, a topic which has been at the centre of my research in the last four or five years, and which has thankfully started to gain traction in recent years through initiatives such as the multilingual Open Methods initiative, multi-language versions of the Programming Historian and multilingual DH. As Quinn Dombrowski remarked recently, “Multilingual DH is suddenly blooming”.

I asked colleagues from the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London to describe research they are doing on multilingual digital studies. What follows are a few examples of their work.

Image by Pete Chonka

Far keliya fool ma dhaqdo – one finger cannot wash a face

Or: the problems of mono-lingualism in digital culture studies

Pete Chonka

As a researcher interested in the social, cultural and political impacts of digital media technologies in East Africa, I’m always thinking about the importance of indigenous languages in the dynamic online spaces I study. I often focus on the Somali-speaking parts of this region, and this is a language that I’ve studied and worked with for more than a decade. I’d never describe myself as being fluent – the poetic form of Somali is so rich that I’m still way off full competence there – but I read and speak the language well enough to use it in different aspects of my research.

It’s clear that our field – digital humanities – has a problem with Anglophone monolingualism: the global dominance of the English language. Of course, this is also an issue for Western academia more generally, but because so much ‘cutting edge’ research on digital cultures and societies often focuses on North American or European contexts this compounds the problem. As many scholars have shown, we need to decolonise our approaches and stop universalising Western dynamics and experiences of digital culture as though they automatically reflect people’s engagements with technology worldwide. I believe that thinking carefully about how a world of different languages are used on digital platforms – and how they interact with the ‘algorithmic power’ that so many of us are concerned with – can help with this. As the Somali proverb in the title says, one finger cannot wash a face. I’d argue that this is the same for languages and our understanding of (global) digital cultures – pervasive mono-lingualism can be a huge limiting factor in our studies.

I’ve considered some of these questions in relation to the Datafication and Digital Rights in East Africa network project that I have been involved in over the last year. Our UKRI-funded network has brought together scholars, tech practitioners and civil society activists in and beyond the region to think critically about how digital platforms (and the value of data in East African digital economies, communication practices and humanitarian settings) are influencing societies in that part of the world. Along with colleagues, I’ve been experimenting and thinking through how the vast amounts of data that are generated on online platforms by East African-language users are harvested by these tech companies. To what extent do the algorithms that gather data to target personalised advertising or predict search results ‘get’ the content that is being generated by users writing in a language like Somali? We have to remember that this is a context where the Somali-language is only partially machine translatable – put simply, Google translate for Somali just isn’t very good! What do these linguistic differences mean for the ‘power’ of algorithms to affect how people come across, access and share information on ‘global’ platforms, but in ‘local’ languages? In the work we have done so far on search auto-complete functions in languages like Somalia, Amharic and Swahili, we argue that this is an area that needs much more attention.

The importance of multi-lingualism here is not just about the research itself, but also about how we communicate our findings with wider audiences. Again, the dominance of English in academic publishing is hardly news – though it is certainly a problem. We also have to recognise the continued centrality of English as a regional lingua-franca amongst the kind of researcher, civil society and tech practitioner communities who we work with across different East African countries in our network. Nevertheless, I’ve always tried to make an effort to use my (modest) Somali language skills to share findings from different research projects directly with those affected by the things I study and to reach audiences who don’t necessarily speak English. For example, we have started to complement the English-language blogs produced by and with our network partners with podcasts in languages such as Somali. These are designed to give an opportunity for our contributors to discuss in East African languages the findings they’ve highlighted in their written outputs. We’re still in the early stages of this, but my own experiences (along with insight from our partners) indicate that for many people in the region who do not speak English an audio podcast conversation may be more engaging than a written translation of the work into Somali. That’s not to say that promoting written Somali as an academic language is not important – it is! And so many cultural activists are promoting Somali publishing in the region – but using a variety of formats in multiple languages tailored to different audiences can be beneficial.

Our Datafication and Digital Rights in East Africa project has been affected by UK Government cuts to Official Development Assistance research funding and some of our bigger plans for the future of the network will need to change (that’s another story, and for more on the extremely damaging and disruptive impact of these cuts on global research partnerships see here). Nonetheless, we will continue to experiment with multilingual research ‘outputs’ and learn from our colleagues in the region who communicate with diverse multilingual audiences on a daily basis. We shouldn’t forget that multi-lingualism is the norm rather than the exception in East Africa. It’s a sign of my white privilege that people sometimes marvel at me speaking Somali. In those instances, I always try to emphasise the fact that my language skills pale (as it were) in comparison with so many people in the region itself, for whom multilingualism (in Amharic, Arabic, Af Maxaa Tiri Somali, Af Maay Somali, Kikuyu, Kamba, Oromo, Sheng, Swahili… the list goes on) is just part of daily life. Western academia needs to catch up and think more seriously about how multilingualism affects digital cultures in different ways around the world.

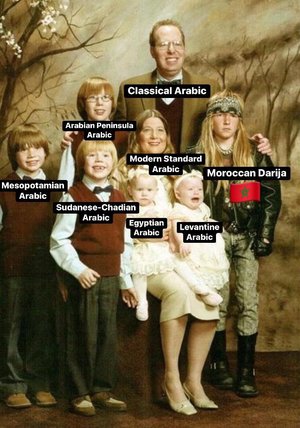

Popular facebook meme

Digital Languages: The Case of Darija

Cristina Moreno Almeida

My line of research at DDH is focused on popular digital culture in North Africa, more precisely Morocco. I look at multimodal online cultural production such as memes, animated cartoons or music videos which normally employ a language quite distinct from Arabic, the country’s official language. The online cultural production I analyse is mostly in Darija, a language most Moroccans use in their everyday lives. Darija is frankly quite difficult to define with a few words. Without falling down the rabbit hole of Moroccan sociolinguistics, Darija can be described as having common grounds with Modern Standard Arabic, but with important grammatical differences including words derived from Tamazigh (Berber), French, Spanish and more recently English. There are local variants, some of which are associated with social class, complicating the matter even more. Although Darija has sometimes been described as an oral language, one can find texts written in Darija. However, it is in the era of social media where Darija has reclaimed its central status as the ruling language of the Moroccan internet. Darija is dominant on Facebook comment sections, YouTube videos, Instagram Stories and TikTok. It is precisely the penetration of internet and ICTs from text messages to social media that has propelled such an amount of oral and written text in a language that is still not official in Morocco. Initially, many of these texts in Darija, and for that matter all the other local languages written by users within the Arabic speaking world, employed an alphanumeric Latinized Arabic because of technological deficiencies for non-Latin characters. Advances in technology have made exchanging languages and alphabets on our digital keyboards easier leading to a wider use of the Arabic characters. An added complication in the use of two different sets of characters is that as a non-official language Darija lacks a normalised grammar. Therefore, words may be spelled differently, complicating any research in this language, for example affecting searches on relevant words or hashtags on Twitter. A further complication in researching online cultures in Darija are the use of neologisms especially concerning young people’s language use. While there are a few bilingual dictionaries of Moroccan Darija into English, French and Spanish, these have not been able to keep up with contemporary youth. Automated translations and transcriptions are useless as they cannot decipher this language. During my work on Moroccan rap, I termed this variant Street Darija or Darija dyal zan9a in contrast with other more enhanced and literary forms of Darija used in formal situations, magazines, poetry and other literary genres. This variant of Darija is mostly differentiated, although not uniquely, by the use of slurs and perceived as popular, as well as more virile and tough. Because Street Darija denotes a certain authenticity in reflecting the real talk, it bestows credibility to those who use it in their expressive cultures. This is the case with comics, rap music, movies, or animated cartoons which dare to jump the hurdles of what is deemed to be socially acceptable in public spheres. Online, Street Darija is employed profusely on discussions taking place on social media especially within groups mainly inhabited by young people. Research in this area is of great significance precisely because this language and its more youthful variant remain unofficial. My research at DDH seeks therefore, at its core, to shed light into the ways in which an unofficial language like Darija, and Street Darija as its most loyal variant to everyday youthful life, has evolved side by side with social and digital, media morfing into different forms and resisting attempts to be cornered as an unimportant language in the so-called age of the anglophone.

Disrupting digital monolingualism

Paul Spence

How can, or should, the digital humanities address the challenges for multilingualism and transcultural dynamics which influence our interaction with digital media and spaces in the twenty-first century? In June last year, a group of us organised the ‘Disrupting Digital Monolingualism’ workshop, to address what some have called ‘language insensitivity’ or ‘language indifference’, in digital studies and practice. Originally intended primarily as a face-to-face event, due to Covid 19, this became a two-part online event which aimed to do two things:

- To showcase existing initiatives in multilingual and transcultural digital studies and practice

- To collectively propose new models and solutions

The first part of the event consisted of lightning talks, demos, posters, a panel and a workshop, addressing everything from digital responses to language endangerment and script displacement, or digital homelands for diasporic languages, to Multilingualism as an instrument for fostering diversity in South Africa. As you can see from the videos of the event https://languageacts.org/digital-mediations/event/disrupting-digital-monolingualism/ddm-workshop-videos/ (also available on our YouTube channel), the event brought together a wide range of different disciplinary and practical perspectives, from sociolinguistics and language documentation to digital cultural criticism, language education and machine learning. The purpose of the event was not to narrowly define how we should address linguistic and cultural diversity in the digital humanities (and digital studies/practice more generally), but to increase visibility for multilingual digital studies/practice and start to overcome the disciplinary fragmentation which defines much of the discussion around digital mediation of modern languages and cultures, by drawing together different perspectives.

In the digital humanities, as in other areas of digital study, discussions around ‘language + digital’ tend to focus on perspectives from linguistics or on how ‘digital’ disrupts ‘languages’. Here, we aimed to flip this around, and examine how ‘language perspectives’ disrupts ‘the digital’. The speakers were all, in their own way, disrupting digital monolingualism.

The second part of the workshop aimed to build on state of the art presentations in the first part by bringing together leading researchers, educators, digital practitioners, language-focused professionals and policy makers to address the challenges of multilingualism and transcultural exchange in digital spaces, and to propose key areas of strategic development in multilingual digital theory and practice.

We grouped this discussion around four areas, and we invited two facilitators per theme to organise responses to a series of starting questions for each theme, over a one-week period in June 2020. The themes we chose are listed here:

- Linguistic and geocultural diversity in digital knowledge infrastructures

- Working with multilingual methods and data

- Transcultural and translingual approaches to digital study

- Artificial intelligence, machine learning and Natural Language Processing (NLP) in language worlds

The facilitators for each group defined their membership and their own terms of reference, each taking a different approach to their methodology: so, for example, some groups consisted of a one-off meeting, one organised a series of daily prompts which members responded to in a writing sprint, and another organised a public survey.

I won’t summarise their work here – that is already summarised on the theme group summary pages – but I do want to draw attention to the enormous amount of work which was carried out by a large group of people (due to Covid-19) at short notice, virtually, and in a short space of time (a week). The drawn-out effects of lockdown and home schooling slowed down our progress considerably, but at least two groups plan to publish final reports soon, and we believe they offer an extremely valuable glimpse of the challenges in undertaking multilingual digital studies and practice which we currently face, and which affect us all.

25 speakers with institutional affiliation in twelve different countries took part in the synchronous event over a day and half (with over 100 other participants most of the time), and the theme groups included 41 participants based in 16 countries. The Disrupting Digital Monolingualism workshop foregrounded the need to more frequently bring together a wide variety of different dialogues, covering such topics as: debates about endangered languages; the role of language disciplines and professions; multilingual digital research infrastructure; localisation in digital media; decolonising the internet; multilingual/multicultural perspectives on the role of Artificial Intelligence and machine translation; and global digital humanities. It also gave testament to the sheer breadth of perspectives which need to come into play when exploring digital linguistic and cultural diversity. It demonstrated the potential for new collaborations between diverse stakeholders who do not necessarily have enough opportunities to engage with each other in exploring these questions. Finally, it highlighted the need to promote alliances between academic, commercial and third sector respondents, as well as the language communities themselves, in responding to these questions and effecting the co-design of conceptual frameworks, whitepapers, prototypes and toolkits.

Co-ordinated by Paul Spence, Renata Brandao and Naomi Wells, the workshop was hosted by the Language Acts & Worldmaking project with the support of the Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community project, both projects funded by the AHRC as part of its Open World Research Initiative.

This blog post is loosely based on a recent presentation by Paul Spence at the Global Digital Humanities Symposium.

The Digital Modern Languages seminar series

Paul Spence

Naomi Wells and I launched the Digital Modern Languages seminar almost two years ago, with a presentation by Claire Taylor on ‘Points of Intersection: Digital Modern Languages’. We’d been heavily influenced by the work of Claire and others approaching the topic from a Modern Languages perspective, including an article by Thea Pitman and Claire Taylor exploring the “Relationship between Modern Languages and Digital Humanities, and an Argument for a Critical DHML” and a “Shape of the Discipline” writing sprint (the actual writing sprint texts are still available) which looked at seven factors affecting the digital turn in Modern Languages (ML) including (big) data, digital archives, digital as object of study, digital ethnography, users and interfaces and digital mediations of the ML research process. But we’d also been prompted by other perspectives – including global digital humanities critiques, language education, sociolinguistic studies on the multilingual internet and digital language diversity initiatives – to take a more expansive view on the topics we wished to cover in the seminar, and to also incorporate practitioner perspectives and collaborations beyond Higher Education.

The template for our series was taken from the excellent Digital History and Digital Classicist seminar series and we aimed to host events in a variety of formats with a primary focus on languages other than English (and covering both European and non-European languages). Since lockdown, the series has consolidated itself as a virtual seminar which has had a far more international audience than we initially thought possible.

In the two years since the series launched, we have hosted ten seminars, recently averaging over 100 people each. These have covered the following topics:

- Digital modern languages as intersection

- Endangered languages

- Digital mentoring of language students

- Arabic book history

- Remote primary school language learning in lockdown

- Critical digital pedagogies/tutorials

- Digital East Asian studies

- Three early career researcher seminars

We have also published many of the videos from these seminars on our YouTube channel, posted numerous blogs on the ‘digital modern languages’ theme and hosted the Disrupting Digital Monolingualism workshop.

The massive global interruption of the last year has highlighted both the potential and the risks in using digital media for language education and practice, while accentuating concerns around linguistic and cultural diversity in digital interactions. We hope, with this seminar series, to continue exploring the transformations in modern languages (broadly conceived) and sister disciplines such as area studies, linguistics and education studies, and to contribute to wider debates about the impact of digital culture and tools on the way in which we communicate, translate, study and carry out research.

You can find a full list of DML events here https://digitalmodernlanguages.wordpress.com/events/

This series is part of the AHRC-funded Open World Research Initiative, and has been supported by the Cross-Language Dynamics: Reshaping Community and Language Acts and Worldmaking projects, and by the AHRC Leadership Fellow for Modern Languages (Janice Carruthers). The series is convened by Paul Spence (King’s College London) and Naomi Wells (Institute of Modern Languages Research).